I went to the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (YCAM) to see Ikeda Ryoji’s new "datamatics" installations (on show until 5/25). I chose 3/1, the first day of the exhibition, as there was a performance of the audiovisual concert "datamatics [ver.2.0]" in the evening. The exhibition, consisting of only three installations but more than enough to literally overwhelm the visitor with a flood of information, and the two-part concert, together displayed clearly the artist’s terminus ad quem. Where he is at present, he is just as alone as the adventurers in the early 20th century were on their polar expeditions.

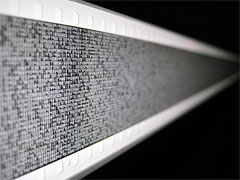

The first thing that greets the visitor upon entering the darkened Studio A is a slim, horizontal belt of white light on eye level, which on closer inspection turns out to be an LED light box about four centimeters in height and ten meters in length. After taking a step closer I noticed a 35mm filmstrip mounted inside the box, and when looking even more carefully, I recognized tiny numbers on the film. I don't know what they are supposed to mean, but these vast amounts of numbers are seemingly arranged in random order. Those who saw Stanley Kubrick’s "2001: A Space Odyssey" the sight will probably remind of that disturbingly mysterious black monolith that appeared all of a sudden in midair in the movie.

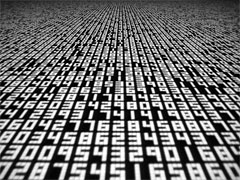

After walking round the light belt, the visitor gets to the interior of Studio A, where fast, rhythmic sounds a bit like a nervous tic here and there overlap with short sine wave sounds. Visible is nothing but a wide and empty, black space, in the depth of which only one wall is emitting strong light. Although red and blue rays appear for brief moments, there are basically the same black and white patterns that are used also in the installation in the entrance area. One can see countless line segments moving up and down, assumedly based on some kind of relational principle, while tiny, square picture elements rhythmically appear and disappear. At the end, the numbers invade this part as well, ultimately turning the screen into an ocean of digits.

Studio B on the second floor is darkened as well, and there are eight monitors and 16 speakers arranged on the floor. The speakers emit varying sounds ranging from deep bass to barely audible high notes (or from low-frequency sound to ultrasonic sound beyond the audible spectrum?), all of which are so sharp that they seem to be chopping up the air inside the venue. Visuals and sounds are exactly synchronized, while test patterns as we know them from TV shoot across the monitor screens like knifes thrown at an invisible target.

The installations are titled "data.film", "data.tron", and "test pattern". As these all-lower-case titles suggest, the works behind them were made by analyzing, transforming and restructuring data. If it was only this, it wouldn't be much different from how art, films, music or literature these days are fundamentally being created, as that’s basically how artistic expression works. Even most other professions in the world, be it the job of a chef or that of a carpenter, essentially follow the same principle. However, what decisively distinguishes Ikeda’s works from others' is the total amount of handled data, the perfection with which they're handled, and the ideas behind all that. While the three installations ambiguously communicated this, it was the "datamatics [ver.2.0]" concert that definitely changed my presentiments.

Part one of the concert was a beefed-up version of the audiovisual concert that was first performed in June 2006 at Tokyo International Forum. Particularly noteworthy was the second half, in which Ikeda’s sound came across as what I'd call the "ultimate Fourier transform", varying from delicate whispering to the roaring noise of a jet engine. The screen was filled with numbers letters, symbols, dots, lines, wire frames, barcodes and other elements, computer-animated by Matsukawa Shohei, Tsunoda Daisuke, Hirakawa Norimichi and Tokuyama Tomonaga. While the previous "C4I" featured images of colorful sceneries among others, this time’s visuals were almost ascetically abstract, and more or less entirely black and white. Watching the million dots spread and turn in grid-like patterns on the high-resolution screen, I felt as if looking at a huge, exquisite 3-D model of the galaxy.

The monitor was then broken up vertically into 8 segments that looked like little monitors, each of which continued to show the same gushing of data. The faster the movements got, the faster and louder got also the sound as it intricately tangled with sine waves. The aforementioned "ocean of digits" that, accompanied by deafening noise, marked the climax, still gives me deja vus. Just when I began to worry that the entire venue might explode, both visuals and sound dissolved into white noise. Everything transformed from an "ocean" to "sand", while the volume calmed down from roaring to buzzing. After 20 minutes the feast of light and sound was over.

Thanks to requests from Ikeda and the members of Dumb Type during the planning stage, Studio A is one of the top venues in the world in terms of acoustics and equipment. This time (again) the artist’s meticulous orders pushed the YCAM staff "to the limits" when assembling the equipment in order to work out the best possible sound design for the event. The materials Ikeda worked with were "vast amounts of data" ranging from human genomes to surds, in amounts that no human being can perceive - which actually isn't even necessary at all. As Kubota Akihiro wrote in vol. 72 of "intoxicate" magazine, "[He] doesn't expect or assume that people perceive or compute," which means that we're talking about "the having-been-there of the thing" (Roland Barthes/Ohtake Shinro). In terms of both quantity and quality, Ikeda is indeed pushing things to the limit.

This attitude and technique of gathering as huge an amount of data as possible, splitting everything into the minimum units of pixels and sine waves, and reconfiguring those in a way that couldn't be more sophisticated, is of course intimately connected with Ikeda’s motive for creation. His style is often referred to as "minimalist", but to me this classification seems to be telling only half the truth, as Ikeda is certainly pursuing not only the minimum but the maximum as well. While of course being aware that it is beyond human ability, to me it looks as if he was trying to simulate the principle behind the creation of the universe.

After the concert, the night sky over Yamaguchi was perfectly clear and studded with stars. A mutual friend told me that Ikeda once muttered when looking up to the starry sky, "This is one thing that I'll never beat!"

A concert of "datamatics [ver.2.0]" in Tokyo takes place on 3/16 at The Garden Hall.

2008.3.6

Ozaki Tetsuya / Editor in chief / REALTOKYO