As I was appointed General Producer for the Performing Arts section of next year’s Aichi Triennale, I traveled to three European countries between late May and mid June, in order to watch some pieces and meet artists and people from companies that I am considering to invite for the Triennale. I went to Kassel for the "Documenta 13", and visited La Triennale (aka "Paris Triennale") at the Palais de Tokyo in the French capital. My account below is on what I saw in the realm of performing arts exclusively, whereas artists and companies mentioned here don't necessarily have to appear in Aichi 2013.

In Dresden, I watched The Forsythe Company’s performance of "Yes, We Can’t", a dance piece inspired by Samuel Beckett’s phrase "Try again. Fail again. Better again." in "Worstward Ho". Unfortunately the performance was ill-fated, as three dancers were infected with the Mono virus shortly before the event, and were thus unable to perform, forcing Forsythe to rework the piece’s composition and choreography. The result was definitely different from what I had seen on YouTube and elsewhere before. But even though the choreography had changed, and there were hardly any dialogues or songs, the trials and tribulations that the above-mentioned phrase suggests were brilliantly expressed through movements that were somewhat awkward at first but looked much more handsome in the latter half. However Forsythe himself was obviously not satisfied, as he looked back on the performance with a bitter smile, calling it "an expensive rehearsal." According to the dancers, "Bill must have been happy considering that he always wants to change things around anyway. The piece will surely continue to change." Forsythe has always been insatiable as a choreographer.

The "Holland Festival" in Amsterdam once again boasted a powerful lineup. My schedule didn't allow me to catch the alleged highlights, Robert Wilson’s "The Life and Death of Marina Abramovic" and William Kentridge’s "Refuse the hour", but the rest of the program was magnificent enough, showing just how dense and rich the art scenes in the West are. Alain Platel packed the stage with a chorus of approximately eighty members recruited from the general public, in addition to the Teatro Real’s orchestra and singers, to confront the ten dancers of his own Les Ballets C de la B in "C(h)oeurs". I would say it was very suited as a method to express the piece’s "Arab Spring" sort of general theme, "individual vs. collective" or "esteem and acknowledgment of individuality and diversity". Alternating choruses by Verdi and Wagner, sung live and loud on stage directly into the viewer’s ear, was quite an impressive feat.

Boris Charmatz’s "enfant" was rather thinly layered, but the central theme was crystal clear throughout. When the curtain went up, the stage was dotted with children lying motionless like dead, and grown-up dancers trying to wake them up. For a while the children didn't seem to wake up, but when they finally did, they joined the dancing crowd and eventually gathered so much steam that they even surpassed the adult dancers, who in turn slowed down and finally ended up lying on the floor, just as still and seemingly unconscious as the children did before. For Charmatz, who used to play a central role in "non-dance", this work marks a complete about-face, as he makes the dancers move strenuously and dash at full speed across the stage this time. Like the voices in Platel’s "C(h)oeurs", the bodies in "enfant" are fully charged with power and intensity.

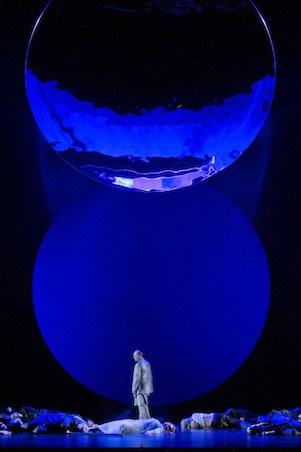

One positive surprise came in the form of Pierre Audi’s rendition of "Parsifal". I'm not a big Wagner fan, and I'm anything but an opera maven to begin with, but I decided to go and watch it nonetheless because I heard that sculptor Anish Kapoor was in charge of the stage set, and Jean Kalman did the lighting. They absolutely lived up to my expectations, and especially the second act was really overwhelming. Faint white smoke was hovering on the otherwise totally empty stage, when a giant moon and its shadow came down from above. In fact, what looked like a moon turned out to be a concave mirror six meters in diameter. Moving vertically and horizontally suspended by wires, the mirror appeared like a perfect circle, or looked egg-shaped depending on the angle. In concert with the events on stage, the lighting turned blue to create a magically fantastic scenery. The darkened auditorium, the actors on stage, and the white sheets of music in the orchestra pit was about all that could be seen in the mirror, however what the viewer could recognize there was nothing but the downright reality. The mirror as a device that reminded the audience of the fact that "this is fiction" functioned in a properly Beckett, Agota Kristof or Abbas Kiarostami kind of way. Both props and lighting were kept simple and minimal, but with maximum effect.

Speaking of mirrors, Jérôme Bel’s "Disabled Theatre", one of the few pieces I caught at the Documenta, was a work that provided evidence of the statement that "every outstanding work of art is a mirror." The eleven performers entered the stage and briefly introduced themselves, after which seven of them presented solo dances of about three minutes each, to music of their own choice. After that, each of them commented on his/her performance, and finally danced again. That’s about it. All of the eleven performers, however, have learning disorders. Although handicapped, all of them are actors and actresses of a Zurich-based professional theatre company, and the dance parts this time have been choreographed by Jérôme Bel, so quite naturally they were beyond comparison to the average "normal" person with no performing experience (such as myself). But nonetheless, I wouldn't call their movements "naturally flowing". While watching the piece, all kinds of thoughts and questions crop up inside the viewer. "Able-bodied and disabled – we're all the same after all and should live together in harmony (or maybe it’s just a display of political correctness?)." "Their enthusiasm deserves praise (or maybe that’s just hypocritical?)." "What a wonderful work full of humanitarianism (or maybe it’s just an unscrupulously low-level spectacle?)…"

Meanwhile, the performers made some insightful remarks afterwards, like "my mother said it looked like a freak show at first, but at the end she really enjoyed it," or "my sister commented, 'you looked like animals in the jungle, but I liked it!'"

Different people will probably interpret these words differently, and in the end provoking such varied reactions is probably just what Bel intended when writing the piece. What each spectator sees on the stage is not "a pure showcase of the playwright’s world-view." After all, what is there is a mirror, and that mirror reflects our own internal aspects. Like the works of Platel and Charmatz, this one is themed around "esteem and acknowledgment of individuality and diversity" as well. That diversity is always just as large as the audience, and exposing that and making us aware of it is not exactly a task that anyone can accomplish.

(June 29, 2012)

Ozaki Tetsuya / Editor in chief / REALTOKYO