Artist Yanagi Miwa, whose works in the realm of fine art have been displaying strongly dramatic and narrative qualities, has recently turned rapidly and very seriously toward theater.

Her first stage production, "1924 Naval Encounter" (11/3-6 at Kanagawa Arts Theater) is part two of the "1924 Trilogy", the first installment of which, "1924 Tokyo-Berlin", was staged in July in Kyoto. Protagonist is Hijikata Yoshi, who set up the Tsukiji Shogekijo (Tsukiji Little Theatre) as a 26-year-old in the year after the Great Kanto Earthquake. The venue was formally opened with the first ever performance in Japan of German expressionist playwright Reinhard Goering’s "Naval Encounter (Die Seeschlacht)" under Hijikata’s direction. Fifty years later it was staged once again by Tsukiji founding member Senda Koreya, and only a few times since.

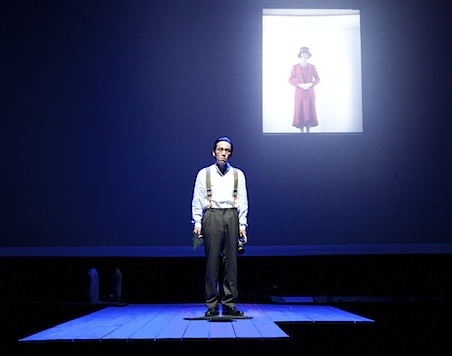

Upon entering the Kanagawa Arts Theater’s Large Studio, visitors were guided to their seats across a stage that represented "the stage at Tsukiji just prior to its opening." While this isn't exactly a new method of leading the audience into the theatrical world, having guiding "usherettes" wearing elevator girls' uniforms was a unique and very Yanagi-like idea. As you may know, "Elevator Girl" was Yanagi’s breakthrough work as an artist. Among the usherettes, Yamamoto Maki was particularly outstanding when, like in the previous piece, she narrated with the voice of a professional storyteller at the end of the piece.

The background of the story is illustrated in the beginning by that very "elevator girl". Hijikata (Kanegae Yasuhiro) and the usherette are boarding the elevator of the Ryounkaku (lit. "cloud-surpassing pavilion"; commonly known as "Junikai", lit. "twelve stories") in Asakusa, which collapsed in the Great Kanto Earthquake. The first floor is dedicated to Kabuki, the third to commercial theater. Then come floors showing naturalist and French classical theater among others, before the elevator finally reaches the seventh floor under the banner of German expressionism. Although the elevator can't go further up due to earthquake damage, Hijikata requests to go up to the topmost floor – Russian avant-garde. On the question, "Is there anything above that?" the usherette replies, "If you wish," and maneuvers the elevator further up. This arrangement suggests a developmental historical view that supports modernization and the formation of nation states, and hints at the upward mobility of the modern human.

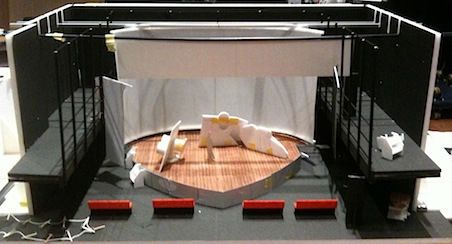

The stage set is dominated by the colors black and red. As a matter of course, these colors reminiscent of iron, fire and blood are symbolizing revolution. The time is shortly after the Russian Revolution. Hijikata, who invested a huge amount of his own money in the establishment of Tsukiji, was later given the title "The Red Count". "Naval Encounter" is anti-war theater, and the play within the play is set on the cannon deck of a battleship. Its creator took the original material and superimposed naval combat scenes in the Sea of Japan during the Russo-Japanese War, and designed the gun turret and cannon deck based on the battleship Mikasa that still exists as a museum ship in Yokosuka.

I suppose the fact that Yanagi chose the young nobleman Hijikata as protagonists, and not Osanai Kaoru, the theoretical support behind Tsukiji, has to be accredited to the artist’s fancy for tales of wandering aristocrats. When talking to her about one month prior to the performance, she explained that she was rather fascinated by an episode according to which watching a piece by Meyerhold in Moscow on the way back home from Germany, where he had studied for a year in 1923, the year of the earthquake, was an experience that changed Hijikata’s life dramatically. Osanai saw Meyerhold’s work in Moscow as well, and even met him in person. However that was several years after Hijikata’s travel, at a time when the Soviet Union was moving forward with the totalitarian scheme, and the masters of constructivism were losing steam. Osanai didn't hide his disappointment when he stated, "I should have gone to Moscow at least three years earlier!" (Soda Hidehiko, "Osanai Kaoru and 20th Century Theater")

As opposed to Hijikata, portrayed as a romanticist who lived and died in his dream, Osanai (Seki Teruo) is caricatured as a person that travels back and forth between ideal and reality. While advocating artistic supremacy, he begs Hijikata for money that he eventually spends on women. He orates critically against (then) mainstream realist theater, but at the same time he uses his iPad to promote the show via Twitter (the iPad and Twitter idea reportedly came from Ago Satoshi, who assisted with the script and direction. The 1920s were also a time when the radio was conquering the world as a new medium.) It is Osanai who personifies themes that have always been conflicting, such as "art and politics", or "expression and revenue".

It must have been the scenery of a conversation between Hijikata and Osanai shortly before his death that Yanagi wanted to depict first and foremost. When Osanai spoke to Hijikata about the Tsukiji Shogekijo’s program for the coming year, mentioning Hijikata’s plan to stage pieces by proletarian playwrights, he made the following remark that may even be considered as a testament. "I won't object, as long as you show quality plays in terms of dramaturgy. However be reminded that Tsukiji is a theater for art." This little episode became widely known through Hijikata’s article "Haiiro no Tsukiji Shogekijo" (in "Shutsuensha no michi"). Nevertheless, after Osanai’s death, Hijikata picked up plays in the style of socialist realism, and dedicated the rest of his life to these activities.

"Art or politics" is a question that has been posed not only by Osanai and Hijikata, but that numerous artists including also Yanagi Miwa have been addressing since the Russian avant-garde. My compliments to an artist who deals with this topic face-to-face in times as shallow as these! What I'd like to stress even more than this however is the point that she is building her pieces around the styles of expressionism and constructivism as represented by the likes of Goering and Meyerhold. The history of theater is one of clashes between dramatic and common language, and assuming that this piece (just like Tsukiji in the 1920s) resulted from an opposing or provocative attitude toward today’s prevailing realist theater in this country that depicts people’s everyday life, it is pretty interesting. Asked about this, Yanagi neither confirmed nor denied, but commented laughing, "I don't care much about ordinary things. I like it excessive!"

What is particularly intriguing is the position of the usherettes. There are several scenes in which they turn to Hijikata and say, "Yocchan, you better go home now." This surely is a hint at the mother, or in other words, the pre-modern age. The elevator girl first appeared in the 1920s. In that sense, it is at once a symbolic icon of modern consumer society, and in addition, it combines aspects of narrator and spectator – perhaps meant to represent today’s media society. My only slight complaint is that the usherettes don't really hitch to the fore as one would expect it from a work by Yanagi Miwa.

The usherettes, as I learned, were given important roles to play throughout the trilogy. I wonder what the total picture will look like after watching all three pieces, and in that sense, I'm very much looking forward to part three, tentatively titled "1924 Man Machine"!

(December 09, 2011)

Ozaki Tetsuya / Editor in chief / REALTOKYO