March 11, 2:46 p.m. I'm at the "Quiet Attentions" exhibition at Art Tower Mito when the earthquake strikes. I'm standing in front of a work by Kimura Yuki, Jutta Koether and Arakawa Ei made of metal pipes, and when the pipes begin to shake, I catch myself marveling rather foolishly, "Hey, I didn't know it moves!" In the next moment, it’s getting serious. I rush outside, where I find the large window pane of the 2nd floor terrace in pieces scattered across the floor. The oddly-shaped, Isozaki-designed tower is shaking all over. Two or three minutes later, I'm sitting on the terrace floor among several members of the museum staff, from where I move further down into the inner courtyard as soon as the rolling calms down. When taking a peek into the 1st floor entrance hall, I notice that several pipes of the pipe organ on the upper floor had fallen down to the ground.

As all trains and buses are standing still, I decide to spend the night in the reception hall of Art Tower Mito, which has turned into an evacuation center. In Mito City, the intensity of the quake measures a lower 6 on the Japanese scale, and although there are some casualties, there is only minor damage compared to the devastation in Miyagi, Iwate and Fukushima. However, there is a complete fallout of electricity, gas and water. There are cracks and bumps in the pavement, and in addition, countless bridges crossing Nakagawa River are closed, and traffic lights are out of service, resulting in massive traffic jams. Once the sun goes down the scenery get pitch-black, and all I can see is a starry sky above me.

Next day, same traffic situation. After seeing an announcement on TV stating that Joban Line is operating, I walk to Mito station, but only to find out that trains aren't going further than Toride. I decide to hitchhike to a station that is in service, and am lucky enough to find a friendly couple that offers me a ride. In the car, crawling down the national road toward southwest, we hear the NHK report on the explosion in Rector 1 of the Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant. I later catch a train and manage to return to Tokyo, while the situation in Fukushima develops as reported in the media.

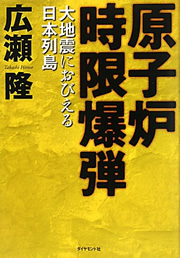

There are loads of things I want to say, but let me just mention one of them. The following is a quote from Hirose Takashi’s book "Time Bomb Reactor" (published in August 2010), in which Hirose raises an alert over the idiocy of erecting nuclear power plants in a zone as prone to earthquakes as the Japanese archipelago. It does not illustrate the recent events. As explained in the text, it’s about an accident that happened nine months ago.

"While I was working on this final manuscript on June 17, 2010, a power blackout just occurred at the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) operated Rector 2 of the Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant, leading to a major accident that almost ended in a meltdown. […] The accident was caused by four external power transmission lines, all of which were cut off at the same time. The emergency stop systems of the generators and reactors did of course work, but as water continued to boil inside the reactors, the cooling water level sank dramatically, and a core melt could only be avoided at the very last minute. […] The fact that something as severe as this could happen even though there was no earthquake on the day of the accident led me to think about what the scenery could look like if the plant was visited by a major quake."

After quitting ART iT Company, for a while I was toying with the idea of making a book on nuclear and solar energy. Although there was a time when antinuclear power movements were beginning to take off across the country, before we even knew it our houses were suddenly powered with nuclear energy – oddly enough, a form of energy that is labeled "clean" only for the fact that no CO2 is emitted. The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, together with the Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, even went as far as to publish a supplementary reader for elementary school kids, titled "Exciting Nuclear Power Land." A bad joke if you ask me, and the thing that mainly inspired my plan.

Another factor was a meeting with Keio University professor Shimizu Hiroshi for an interview for a certain company’s PR magazine. Shimizu is a researcher in environmental issues who is primarily known for developing a 370km/h fast electric-powered car named "Eliica", and authoring a book titled "One Scientist’s Proposal to Mr. Al Gore: With Regards to Solutions to the Problem of Global Warming." The professor’s take on the energy problem is very simple and persuasive. 1: Automobile and iron manufacturing, as well as the use of electricity, are responsible for 95% of CO2 emissions. 2: In order to reduce CO2, we must not continue to rely on fossil fuels. 3: Alternative energies have to be forms of energy that all people can use equally and safely, on a long-term basis, and without triggering new environmental problems. 4: The only form of fundamental energy that fulfills all of the above, and that seems reasonable in terms of cost-efficiency, has to be solar energy.

According to the professor, installing photovoltaic cells across an area equivalent to 1.5% of the (land) surface of the earth would enable seven billion people around the globe to lead a wealthy lifestyle on a level with life in the USA today, even when calculated with a conversion efficiency of 10%. Once the gap between rich and poor disappears, the number of wars and conflicts should decrease, and problems concerning resources such as water and food be solved as well. Even though it surely is a long and difficult way to go, it is definitely a way that is essential for the survival of mankind, and a challenge that is most rewarding to address.

The typical argumentation of advocates of nuclear energy can be found, for example, in the book "The Logic Behind the Safety of Nuclear Power (Revised Edition)" (published in February 2006) by Sato Kazuo, the (then) president of the Nuclear Safety Research Association. He claims that, "For a country with such extremely limited energy resources as Japan, the peaceful utilization of nuclear energy is imperative, in which case, as many will agree, security should be a main premise. This would mean that the question whether or not it is fair to consider existing or planned nuclear power facilities safe enough in regard to this basic premise is not a simple matter of individual interpretation, but all individual positions must be bundled together to ultimately make a judgment as a nation or community."

Well this sounds perfectly reasonable at first, and I'd even replace the word "many" with "everyone" in terms of agreement with "security as a main premise." However, there is a fundamental error in this argumentation. The claim that "peaceful utilization of nuclear energy is imperative" is being presented as an undoubted premise, and that’s the fly in the ointment. Shouldn't the term "nuclear energy" be replaced with "alternative energy", so that it reads something like, "For a country with such extremely limited energy resources as Japan, the utilization of alternative energy is imperative, in which case, as many will agree, security should be a main premise"?

Needless to mention, "alternative energy" refers to possible substitutes for oil, which include not only nuclear energy, but also water, wind, geothermal heat, biomass, and other forms of energy. Solar energy is one of the most promising among them, and given that professor Shimizu is right, it is at once the most powerful and realistic means of power generation. Solar energy is available in virtually unlimited amounts, and without any problems regarding the point of "security". Quite logically, stopping all technical, financial and human investment in nuclear power plants, and focusing on research related to solar energy generation is arguably the only way to improve the situation. That’s what I wanted to get across in the book I was planning.

At this point, it would no longer make sense to publish such a book. However, for Japan in its efforts to recover from the disaster I think it is highly meaningful to seriously consider the generation of solar energy as a means and ultimate goal. When interpreting the things that happened here in Japan as an instructive and enlightening accident that demonstrated the danger and brittleness of societies that depend on nuclear power to the world, to some extent I kind of feel we are just being saved. The enormous number of victims claimed seems a bit too high a price to pay for it though.

Within a few decades after World War II, Japan grew to become an unparalleled economic power in the world. By breaking free from militarism, we managed to accomplish peaceful economic growth so to speak. Consequently, it shouldn't be impossible to forge a major solar power nation by breaking free from the dependence on nuclear energy. While radioactive material is escaping the reactors in Fukushima, some scientists and newscasters made such absurd remarks as saying, "Being able to solve the problem would prove the high level of Japanese technology, so we could sell Japanese nuclear technology to countries in Asia and elsewhere," but I think that’s impossible and plain impermissible. The future of Japan (and the world) depends on solar power and other forms of alternative energy.

PS: According to the Hokkaido Shimbun, Nippon Keidanren chairman Yonekura Hiromasa defended the country and Tokyo Electric Power Company when he gave the following comment on the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in a press briefing in Tokyo on March 16. "Braving a once-in-a-thousand-years tsunami is a magnificent thing. The atomic energy administration should stick its chest wide out." This is in my view another outrageous remark.

Ozaki Tetsuya / Editor in chief / REALTOKYO