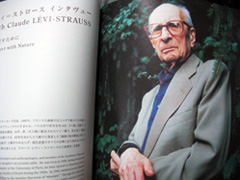

Cultural anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss passed away at the end of October. While the man himself died a peaceful death at the age of 100, he left me with a strong feeling of emptiness.

Ten years ago I had the opportunity to speak with him on two consecutive days. It was an interview for the inaugural issue of "coucou no tchi", the PR publication promoting the Aichi Expo ("Expo 2005 Aichi Japan") that I was involved in as editorial director. The Expo’s central theme was "Nature’s Wisdom", so I immediately thought we'd have to include an interview with Levi-Strauss. Together with Nakazawa Shinichi, who had come up with the theme in the first place, as well as Ito Toshiharu and Minato Chihiro, we formed an editorial committee and went off to France.

As it was the time of his summer vacation, Levi-Strauss was not in Paris but in his residence on the border between Champagne and Bourgogne (Burgundy). As Ito had other commitments at the time, the interview was conducted by Nakazawa, and Minato was put in charge of filming the conversation. Levi-Strauss, who brought along his beautiful wife, walked in a rather wobbly gait, and his hands were quivering slightly, but when we asked him to sign our copies of his book, his tremor stopped as soon as he took up his pen. He spoke logically and methodically, and the tone of his voice was clear and smooth. He definitely didn't sound like a 90-year-old man. In January of the same year, in a birthday party at the College de France, he said the following. "Dans ce grand âge que je ne pensais pas atteindre, et qui constitue une des plus curieuses surprises de mon existence, j'ai le sentiment d'être comme un hologramme brisé. (At this great age, which I didn't think I would reach, and which constitutes one of the biggest surprises of my life, I'm feeling like a broken hologram.)" Such metaphors suggest that he still was anything but senile at the time.

As "coucou no tchi" was a promotional item and not for sale, it isn't easily available to the man in the street. Let me quote here only one of Levi-Strauss’s comments about art. On the question, "It seems that people of today are attempting to grasp once again that kind of expression and technology which is at once art, philosophy, science, and psychoanalysis. What thoughts do you have on this kind of "da Vinci-esque" method?" he answered as follows.

"First, the great tragedy of modern thought is that, in order to survive, humanity has had to sever sensitivity from reason. Structuralism has in fact put all its effort into an attempt to reconcile the two… Second, concerning paintings, I do not think I have made reference to Leonardo da Vinci. Of course, da Vinci was a great genius. As both a scholar and an artist, he is worthy of great respect. For myself, however, his paintings are already on the other side, that is, the side of scientific thought or modern thought. The fact that he was not only a great painter, but also a great scientific thinker, is not surprising. The paintings that I consider most sophisticated and definitive in terms of expression came prior to da Vinci. I find this in the works of the great painters from Flanders and Germany during the early Renaissance: Van Eyck, Van der Weyden, Gerald David, and some others. I feel these were people who understood the link between the senses and reason most of all." (Translated by Yatabe Kazuhiko, Kobata Kazue, Arturo Silva and coucou no tchi)

Levi-Strauss is wrong though when he says he does "not think [he has] made reference to Leonardo da Vinci," as "To a Young Painter" (in "The View from Afar") includes the following line. "As da Vinci profoundly understood, the primary role of art is to sift and arrange the profuse information that the outer world is constantly sending out to assail the sensory organs." (Translated by Joachim Neugroschel)

Be that as it may, Levi-Strauss never acknowledged art from "the other side". It is not necessarily about contemporary (or post-Renaissance) art, but while he valued for example the works of his friend Max Ernst, that was purely because Ernst was a painter who pursued (in Ernst’s own words) "the joy that one feels at every successful metamorphosis… (and which corresponds) to the age-old need of the intellect." In "A Meditative Painter" (in "The View from Afar") he writes, " …as both view painting as successful when it crosses the boundary between the outer and the inner worlds…" (Translated by Joachim Neugroschel) "Both" here refers to Ernst and phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and it s quite obvious that Levi-Strauss was thinking in a similar way as well. The "attempt to reconcile sensitivity and reason" is something that has to be undertaken not only in structuralism, but also in art.

To "One Hundred Years of Idiocy" (Think the Earth/Kinokuniya), which I put together in 2002, Levi-Strauss contributed an essay titled "Redefining of the Rights of Man". It was a short text of 400 words, the first and last lines of which I quote below.

"I was given a long life that covered most of the 20th century. Of the terrible things it witnessed, I shall stress only one: at the time of my birth, the world was inhabited by one and a half billion men; it was two billion when I started working; now it is six billion.

Since Man appeared on Earth, no catastrophe of such magnitude ever plagued other lifeforms. And the only culprit is mankind itself. This is the true and only problem. There is no looking for some specific cause of the direct or oblique origin of the woes of our civilization. […]

Defining himself as a moral being, Man carved himself a special place. Let us found his rights on his quality as a living being, a quality he is not the only one to possess. It is only on this condition that the rights acknowledged to mankind can stop when their exercising imperils another species.

It seems to me that such a redefining of the Rights of Man, reduced to a special case of the Rights of Life, is the necessary prerequisite to this spiritual revolution on which are hinged our future and that of our planet."

Great intellect celebrates identity and detail, and at the same time makes sure to keep an eye on universality and the whole. While praying for his soul, I hope I will be able to take over and convey the spirit of Claude Levi-Strauss in one form or another.

Ozaki Tetsuya / Editor in chief / REALTOKYO