One day prior to the cease-fire in the Gaza Strip, and again one week later, I went to see the "War & Art — Terror and Simulacrum of Beauty" exhibition in Kyoto (through 2/5 at Kyoto University of Art and Design [KUAD], Galerie Aube). The exhibition is held for the third time, following the second installment that featured next to domestic artists the likes of Thomas Demand and Darren Almond. Shown this time are works by six presently active Japanese artists, in addition to a special display of Foujita Tsuguharu’s war painting.

After the war, war paintings have come to be treated as taboo and the "disgrace" of Japanese modern art history. Regarding the latter, painter and novelist Tsukasa Osamu once claimed, "All that emerged from Japanese war paintings was the artists' pride, along with a greater mental poverty than that of 'the ignorant public'. Such works (as paintings of the Greater East Asian War) can impossibly deserve to be valued as works of art. […] If the Greater East Asian War or the Fifteen-year War are the disgrace of Japanese history, then in my view the paintings of the Greater East Asian War are just the same." ("War & Art" 1992) I don't know if such sincere yet somewhat dogmatic sounding objection still applies today, but as a matter of fact, war paintings by the likes of Foujita Tsuguharu have been publicly shown with increasing aggressiveness in recent years.

However, the tendency to taboo exhibitions on "war" themes seemingly still exists. According to independent curator Iida Takayo (head of the International Research Center for the Arts, KUAD), who planned the "War & Art" exhibition, he "couldn't realize the show in Tokyo because of its title’s political vibe." (From an interview in REALKYOTO by Takahashi Yosuke and Shizuuchi Futaba.) As bittersweet as it sounds, in Kyoto he had an easy job thanks to the city’s relatively liberal general atmosphere, and even more so because the exhibition takes place at a gallery operated by the art university where Iida is employed.

More than 20 years ago, something quite similar happened to myself. After joining a major publishing company, the first project I proposed was "a book of mushroom cloud photographs". The plan was crushed on the spot by my immediate boss, who found that "a book like that won't sell," and I was only marginally satisfied later on when I put a photo of a mushroom cloud on the front page of each chapter of a paperback edition of Miyauchi Katsusuke’s nonfiction. Behind my boss’s remark I sensed the same kind of taboo that Iida felt. That’s why I shouted with delight but at the same time was slightly frustrated when "The Age of the Atom" — planned and edited by Kusumi Kiyoshi, and art-directed by Higashiizumi Ichiro — was published seven or eight years later. The same happened again in 2003, when Michael Light’s "100 Suns" appeared.

This sort of taboo does still exist, and in this respect the art world is lagging behind the publishing business. Nonetheless, the works shown at the "War & Art" exhibition include one of Furui Satoshi’s "Mushroom Cloud" paintings, and the same artist’s detailed "Nucleochronology". In a related talk show at KUAD on 1/23, the artist explained, "I started the mushroom cloud series after an atomic bomb exhibition at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum was canceled." His motivation (and reason) behind this series is totally different from that behind Foujita’s war paintings, but it is of course perfectly appropriate for an exhibition on the theme of "war and art".

Time Train to Auschwitz No.3

2008

Fleischmann 5732, HO rail, metal bar, LED, electic wire

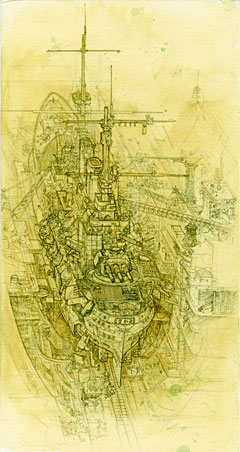

The Imitative Painting of The Sino-Japanese War and The Russo-Japanese War

2002

pencil, pen, warter color on paper

Ultimate Weapon(Monster)

2006

FRP

Other participating artists include Yokoo Tadanori, Miyajima Tastuo, Yamaguchi Akira, Sasaki Kanako, and Ohba Daisuke. Miyajima’s tiny "sculptures" and Sasaki’s video, which are displayed in the same room, share the same "railway" motif. Miyajima’s works involve once again LED number displays counting down, this time integrated in small-scale models of train cars, while Sasaki’s movie shows the artist herself lying on the tail end of a moving train and picking up clothes and shoes from the tracks (the film runs in fact in reverse). In both cases, the cars resemble the Nazi trains bound for concentration camps, recurring images and sounds of which Claude Lenzmann used in his documentary film "Shoah". Other artworks along the same line would be Mordecai Ardon’s " Train of Numbers" and Ono Yoko’s "Freight Train". (See also OoT 008)

While these alone suggest rather clearly the hidden subject, Iida (whatever his true intention may be) doesn't display "anti-war" and "nonmilitant" slogans too prominently. Yokoo’s new paintings, for example, show such personalities as MacArthur or Watanabe Hamako, a popular singer of the Showa era, in addition to phrases like "Ah! So" that Japanese people associate with Emperor Showa. In photographs taken by Shinoyama Kishin, Yokoo himself appears dressed as a kamikaze pilot (with an array of funny corporate logos and brand names on his uniform). Yamaguchi shows "Jujigun", a highly allegoric work dating from 1993 that shows white crusaders on motorbike-shaped horses battling an army of skeletons, and mainly caricature-like drawings of the Russo-Japanese War, most of which are "inspired by Shiba Ryotaro’s 'Saka no ue no kumo (Clouds Over the Hill)'." Ohba shows paintings made with special paint that reflects light differently depending on the viewer’s perspective, and a sculpture of a combat robot kind of object that looks like aggression personified. As these works are displayed next to Foujita’s war painting, it should be clear that evoking a simple dualistic theory of good and evil such as Tsukasa’s is not the aim of the show.

The arms - including the mushroom cloud as a "result"– that emerged from the cutting-edge warfare technology of modern and contemporary science include in many cases a sense of "beautility". I don't know about the thoughts of Furui, Miyajima and Ohba (and it’s certainly presumptuous to compare myself with these artists), but collecting and presenting "beauty" was one of my biggest motifs when planning the "book of mushroom cloud photographs". Needless to say, all "evil" includes a notion of "beauty". While playing on the childishness of boys indulging in war games and plastic models, the Gundam Exhibition a few years ago, and also the works of the Chapman Brothers, definitely share the same kind of purpose: a "pursuit of beauty" as a materialization of desires.

It goes without saying that the world would be a better one without wars. But no matter whether the fighting will continue or not, there certainly exists a sort of sensibility that sees "beauty" in battles and weapons. This gap gives visual art and various other forms of artistic expression the necessary room to grow, and as "political correctness" aims to fill that room by suppressing artists' desires as "taboos", we have to conquer the suppression just as we have to conquer war. I do hope the "War & Art" exhibition will come to Tokyo as well.

Ozaki Tetsuya / Editor in chief / REALTOKYO