As "Shincho" editor Yano Yutaka mentioned in previous articles on RT, novelist Mizumura Minae’s "Nihongo ga horobiru toki (The Fall of the Japanese Language in the Age of English)" (Chikuma Shobo) is currently making waves among the reading public. Summed up very roughly, Mizumura claims that English has come to reign supreme in the age of the Internet, replacing such former universal languages as Latin and classical Chinese. The position of the Japanese "national language" that has been established in the modern age is endangered, and as those hungry for wisdom read and write directly in (the new universal language) English, the days of "national languages" and "national literatures" of non-English speaking countries seem to be numbered. In today’s mass consumer society, books have become low-cost "cultural goods", as a result of which the average popular novel is a boringly mainstream piece of writing.

Mizumura’s discussion and analysis of the formation of national languages and national literatures is quite vivid. Novelist Ikezawa Natsuki wrote in the Mainichi Shimbun, "This is the clearest argumentation I've ever seen." Books written in "the universal language" and understood only by a limited number of people were translated into colloquial language, to establish a written language that a large number of people can understand. Elaborate literary language reaches the level of universal language, and people recognize the "national language" as "their language". At the same time, a national awareness develops among people who use the same language, and national literature comes into existence. Especially interesting is the fact that, while leaning on Benedict Anderson’s "Imagined Communities", Mizumura places emphasis on the aspect of translation.

There are, however, also objections to this understanding of the present situation, especially in regard to the collapse of national literatures. Literature critic Nakamata Akio writes snappishly, "The most inexcusable thing is [Mizumura’s] uncompromising disdain for contemporary Japanese authors who write in Japanese, along with the ignorance her scorn is based on." ("Wrecked on the Sea" blog) "Honestly it’s not very convincing, because if today’s Japanese literature has 'degenerated into a literature of a local language,' that’s possibly what actually makes it attractive for people in the West," writer Ohtake Akiko agrees. ("Kinokuniya Booklog" blog)

There isn't enough space on this page to discuss the downfall of national literatures, but in response to objections to another demand of Mizumura’s, suggesting that "a small bilingual elite be nurtured," I'd like to say that I basically agree. Her claim is not based on mere elitism. The first condition is that "Japanese learn through school education to make proper use of the Japanese language, " and that "everybody is equipped with the basics needed to understand English, the global and universal language." She further proposes, "Japanese individuals that are able to express their ideas clearly in English to international audiences should be fostered," because otherwise the Japanese language is indeed likely to go under.

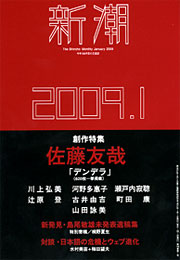

The January 2009 edition of "Shincho" magazine includes a conversation between Mizumura and Umeda Mochio, one of the first to publish a rave review of "Nihongo ga horobiru toki" on the Internet. "There is no need that everybody writes directly for all mankind. I would even venture to say that Japanese people writing in Japanese to highlight the difference between aiming at the abstract target that is mankind and writing for local people render a service for mankind. If all people in the world were writing exclusively in English, we would be living in a very boring world," Mizumura remarked as an adjunct to her publication.

From the standpoint of someone involved in the production of bilingual media, I think that both comments are very easy to understand." Japanese individuals that are able to express their ideas clearly in English to international audiences" are, as Mizumura says, necessary first and foremost in political circles, but also in less money/power-related fields they are desperately needed — if possible in large numbers. Ten-odd years ago, a (Western) artist friend of mine quoted in a text about Japan a Japanese political analyst. The quoted phrase itself was harmless, but when I asked him about what inspired him to quote a person with ideas that are totally contrary to his own, he explained, "Because it was the only text written by a Japanese (in English) on the Internet that I could find." I pay respect to the foresight of a critic who recognized the potential of the Internet in the early 1990s, but the fact that I realized how miserable the situation was is also one reason why we decided to launch REALTOKYO.

The conversation with Umeda was worth listening to, and in relation to that, I would say that it is desirable that the number of translators increases. Or, more precisely speaking, it’s the number of "translations" that should increase. At both REALTOKYO and ART iT we sometimes receive obscure Japanese drafts that are hard to understand. As it is imperative for the translator to understand the meaning of a text in the first place, it happens that we ask the author for clarification, and in cases the article needs to be rewritten, these often result in a significant improvement of the Japanese writing. I don't know how it’s in the realm of literature, but one thing that applies to all other verbal statements is the possibility that both terminology and logic become much clearer when the respective text is to be translated. In addition, the sense of tension (?) resulting from writing something that is likely to be seen by overseas readers possibly helps suppress the inclusion of wild views that are shared only by the writer’s devotees.

Here’s one suggestion. As I said before to "Shincho" editor and RT contributor Yano, one — or better still, every — Japanese literary magazine should be publishing at least one English edition every year. Most of them are monthly, so this would mean that they do eleven Japanese issues a year, and one anthology kind of edition that collects the best contributions. That would be published not in Japanese, but entirely translated into English. Translation fees would be about the same as writers' fees, so budget-wise it shouldn't be a problem. There must be many overseas readers, publishers, agents, researchers and libraries that are eager to read things like these. If our national literature is endangered, and even if the progress is unstoppable, it can at least be slowed down, plus it would be a way to raise awareness of Japanese contemporary literature both in Japan and abroad.

The Agency for Cultural Affairs is doing a "Japanese Literature Publishing Project", but frankly speaking that’s nonsense, because the greatest connoisseur of a nation’s national literature definitely has to be an editor of a literary magazine. For good or bad, literary magazines these days are rather unlikely to produce "average popular novels," so chances that such English editions include "boringly mainstream piece of writing" are virtually low. Even more than that, they should be anthologies that only pick up the stuff that’s really worth reading. What do you think, Yano-san?

Ozaki Tetsuya / Editor in chief / REALTOKYO