I had some business to do in Yamaguchi earlier in June, and when Ushioda Atsuko, a friend of mine, heard that I was going to travel there, she sent me an email telling me about a Yamaguchi resident painter whose work she'd been "totally in love with since four years", and asking me to meet that "absolutely unknown genius painter who made but never exhibited in public about 30,000 works in 30 years." Although her letter was of course slightly exaggerated, Ushioda was basically right, and I can affirm that the man I eventually visited together with her is indeed a genius.

Tagami Masakatsu, born in 1944 in Yamaguchi, remembers that he had been "totally ignorant of art for about 30 years." He further explains, "I didn't like to work, and even though I once had a job in a furniture shop, I didn't stay long… I was living off my parents for quite a long time (laugh)." The turning point came when he was 29 years old, and decided to take drawing lessons because he suddenly felt the urge to draw nude pictures. Increasingly captured by the fascination of drawing, in the following thirty-odd years up to his 64th birthday he made "somewhere between 25,000 and 30,000 artworks," Tagami reports in a straightforward manner and without any particular expression on his face. It was the same smiling face that appeared in the documentary video that musician Pierre Barouh, Ushioda’s husband, once made of the artist.

Media, techniques and materials he utilizes range from drawing and oil painting to etching, drypoint, engraving and calligraphy, and from canvas and drawing paper to wood, poster/wrapping paper, chocolate boxes, and even lids of canned dried seaweed. In his oil paintings he partly uses Japanese paper to create relief-like surfaces that place these works somewhere between two-dimensional painting and sculpture. In the first drawing class he attended, Tagami learned not only how to work with oil paint, but he also familiarized with engraving and other tools. However, as none of his teachers really taught him any techniques, he independently got everything from books.

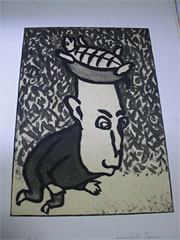

The subjects and styles of his works are multifarious. Probably the results of his studies at the time, his early paintings are somewhat reminiscent of the likes of Bosch, Bruegel and Goya. Here and there I spotted also pieces that made me think of A.R. Penck or Paul Wunderlich, to name a few more recent artists. Then there are sketches that look a bit like the Zen paintings of Hakuin or Sengai. While these must be imitations made during his study phase, the dynamic and pretty overblown facial expressions in his later works display a significantly increased degree of originality, which shows how, along with the technical improvement, Tagami gradually developed his very own style of artistic expression.

Another thing that looking at Tagami’s works made me realize is the absurdity of such categories in art as "insider" and "outsider". His lack of "proper" art education would place Tagami in the category they call "outsider", whereas "proper" education here means having studied at an art university. But even though Tagami hasn't studied art history in lectures and courses, an indirect influence is clearly and quite strongly reflected in his paintings. Especially his most recent efforts are absolutely "readable" in the context of contemporary art. They might be so powerful and expressive in both color and composition that they don't even have to be read, and here and there involve the possibility of being misinterpreted, but "readable" they definitely are. That’s actually what distinguished them from art brut.

Anyway, what’s much more overwhelming than this is the quality and the sheer amount of paintings and drawings Tagami has produced. In her email, Ushioda Atsuko wrote that Tagami is "absolutely unknown" and his works were "never exhibited in public", but as a matter of fact, he did some solo exhibitions and participated in a few group shows in various rural cities as well as in Tokyo. While he isn't really known here in the capital, there seem to be some hardcore fans in other parts of the country. But the above-mentioned amount of his works can of course not be introduced in small galleries, and as he isn't affiliated with any primary gallery, it would be unfair to say that Ushioda was totally wrong with her comment.

In terms of prolificacy and stylistic variety, such people as Ohtake Shinro come to mind, but Ohtake’s Musashino Art University background makes him a splendid "insider". Tagami is perhaps more comparable to Emily Kame Kngwarreye, whose retrospective exhibition is currently on view at The National Art Center, Tokyo (through 7/28). Kngwarreye was born around 1910, and grew up based on Australian Aboriginal tradition until - after some attempts in batik printing- she began to paint in 1988, when she was almost 80 years old. During the eight years up to her death in 1996, she made an estimated 3,000-4,000 paintings. Even though the artist never had any connection to Western art in daily life, a large part of her extremely abstract paintings show surprising parallels. One difference is perhaps that there Kngwarreye’s paintings aren't divided into upper and lower, left and right halves (which is probably due to the fact that she painted onto canvases lying flat on the floor).

148 x 195 x 65 cm

Hirata Isshiki Hozon Kyokai

Izumo City, Shimane

Then there is the "Hirata Isshiki-kazari", a local tradition of Hirata (now Izumo) in Shimane Prefecture, which dates back to the Edo period. It is said to be a habit that has its origins in a statue of Mahakala (or Daikokuten, the god of wealth) that a certain picture framer made using a set of tea utensils, to offer to Tenmangu in 1793 as a prayer for protection from a plague. The technique he introduced has nowadays reached the highest degree of perfection. Every year in July, when the city of Hirata celebrates the Tenmangu Festival, volunteer artists present their "new creations", two of which are currently part of the "Kazari - The Impulse to Decorate in Japan" exhibition at Tokyo’s Suntory Museum of Art (through 7/13). One of the most outstanding contributions is a giant shrimp assembled exclusively from bicycle parts. In my opinion, its excellent workmanship easily outperforms that of Choi Jeong Hwa, Yodogawa Technique, or even Arman. Also from a creative viewpoint, this piece is a truly beautiful assemblage.

Made with bicycle frames, headlights, saddles, spokes, tires and other parts, the shrimp hints at such issues as the evolution of industrial art and mass production/consumerism, environmental problems, and the eco boom of recent years. Art-historically, the one could place the artist on a level with the aforementioned artists, as well as the likes of Kurt Schwitters, or ready-made master Duchamp. Although it was made for ceremonial purposes and offered to a shrine, if exhibited in a museum of modern or contemporary art, you could ask a hundred people and I bet they'd all classify it as "contemporary art".

The works of the artist I introduced above make perfect study material when giving another thought to the eternal question, "What exactly IS contemporary art?"

Ozaki Tetsuya / Editor in chief / REALTOKYO